Glossary of Terms

Table of Contents

Theory of Change

The way an individual or organization conceptualizes how and why social change happens. For example, believing that change happens when we convince individual legislators to support an agenda is a different theory of change than believing that change happens when average people make demands of power-holders and stop cooperating with the status quo until they are met.

Movement Ecology

As fish in water, we sometimes forget not only the culture we’re swimming in but also the larger ecosystem we’re part of: beyond our organizations, there are many campaigns, movements, cultures, communities, and institutions that are trying to make change in their own ways. The dominant culture of isolation and individualism can confuse us into thinking that we are alone at the center, rather than integrally connected to a network of changemakers with diverse theories of change. Ecology shows that diversity and mutualism -- rather than monoculture and antagonism -- are the conditions for strength and survival. If we saw our work ecologically, we would be more supported and more successful.

Movement ecology is useful not only for appreciating different theories of change, but also for explicitly acknowledging our own individual biases toward a specific theory. If people within your organization or movement aren’t in agreement about a theory of change, it is very difficult to come up with a winning strategy and carry it out in a unified way.

We see 3 main theories of change at work within our movement ecology:

Personal Transformation

This theory of change believes that when we are hurt and suffering, we are more likely to inflict hurt and suffering on the people and projects around us; conversely, when we heal these hurts and take a step toward personal liberation, wellness, or enlightenment, we are more capable of healing and supporting those around us. The site of personal transformation is the individual.Alternatives

Within Alternatives, we have alternative institutions and alternative cultures. Alternative institutions create change by experimenting with alternative ways of doing and being in the world: time banks, worker cooperatives, communes, monasteries are some examples. All of these push the boundaries of what is possible within our social landscape. Alternative institutions provide the material conditions for us to relate to each other in a way that is aligned with our deepest values, instead of values compromised by the options of the status quo. Part of this theory of change is that successful experiments not only foster the wellbeing of those who participate in them, but in some cases they prove the success of innovations and thereby lead the way toward broader changes in law and policy. That said, alternative institutions are generally private, meaning they tend not to depend on the state (and often occur in spite of it). Alternative cultures don’t always exist within a single institution, but are a form of cultural innovation. Artists, musicians, and community-creators are often critical for seeding alternative cultures, which can provide another kind of support to exist in a way that is different from the status quo.Changing Dominant Institutions

Structure-based organizers and mass protest activists, alongside policy advocates, electoral campaigners, lobbyists, and lawyers focused on impact litigation, all subscribe to this theory of change. They believe that by reforming dominant institutions-- such as governments and corporations--they can change life more significantly and for more people than by other means.

As an institution, Momentum is geared toward those doing dominant institutional change, but healthy movement ecology includes other actors doing the work of personal transformation and alternative institutions. Healthy movement ecology frees us from the burden to embody every theory of change ourselves; it allows us to honor our unique role in the ecology while being in collaboration and mutualism with others.

Two Organizing Traditions

Within dominant institutional change, grassroots organizing occupies an essential role: if you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’ve committed your life to grassroots organizing because you understand it as the most effective means for regular people like us to reshape society and restore wholeness to the individual, the community, perhaps the world. Within the U.S., we have two major traditions of grassroots organizing: in Momentum we call these structure-based organizing and mass protest. If you’re an activist in the U.S., chances are you were brought up through one or both of these traditions.

Structure-based organizing is our catch-all term for organizing which tends to target a decision-maker (i.e. an elected official, a boss) with an instrumental demand (i.e. a new policy or piece of legislation), and to create leverage over that decision-maker by building a base. Structure-based organizing typically starts with winnable issues that the constituency cares about, such as installing stop signs or speed bumps, and prepares a base for these campaigns through 1-on-1’s and deep leadership development. This tradition finds articulation in Saul Alinsky’s writing (such as Rules for Radicals), and has been institutionalized through well-known organizations like the IAF, PICO, ACORN, and training institutes like Midwest Academy and People’s Action. The undergirding theory of change of structure-based organizing is that if we win small demands in the short-term, activists will have an experience of victory which in turn grows the base and allows us to win larger demands over the long term in a virtuous cycle.

Mass protest, on the other hand, refers to a tradition of disruptive action that publicly expresses outrage and urgency around a given issue. Mass protest runs the gamut from local, disruptive actions, such as the 1960 lunch counter sit-ins during the civil rights movement, to actions that spread like wildfire across the country, as we saw with Occupy in 2011. A core feature of this tradition, however, is that it attracts and mobilizes the general public: the people who show up at an action have not been turned out through a series of phone calls by staff organizers, but are instead mobilized through word of mouth. Examples of this include the 1963 Children’s March in Birmingham, the 2006 immigrant marches, the 2014 protests in response to Eric Garner’s death, and the 2017 Women’s March. Mass protest’s core theory of change is that disruptive action with popular demands will polarize the public and, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “dramatize the issue [so] that it no longer can be ignored.”

Though the reality of diverse organizing efforts does not fit neatly within these two traditions, we find the schema helpful in illuminating the fact of lineages in U.S. organizing, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of each lineage: structure-based organizing is able to develop deep leadership in the base, plan and win incremental campaigns, and sustain action over the long term, but is limited to winning what the political conditions permit and is unable to scale without staffing up. By contrast, mass protest is able to activate far greater numbers of volunteers through decentralized networks and can change the political weather to make new demands winnable, but tends to have trouble sustaining itself over the long-term, maintaining unity internally, or securing concrete reforms.

This is why Momentum proposes a hybrid model which integrates the best of both traditions to overcome the limitations of each. There have been numerous instances of hybrid models throughout history, including the Indian independence movement, the South African anti-apartheid movement, the civil rights movement in the U.S., and the Serbian student movement Otpor. What makes these movements unique is that they were able to scale and sustain themselves without staffing up; plan disruptive campaigns that changed the political weather; and win sweeping, previously unimaginable reforms. While the media tends to represent movements as unplanned eruptions caused by a perfect storm of conditions, organizers and social scientists alike have shown over and over again that skills and strategies are a determining factor in whether movements win or lose-- and that winning movements change the political weather instead of simply responding to it.

The Cycle of Momentum

In order to shift popular opinion, we need momentum: in other words, increasing numbers of people escalating together over time. Movements can generate momentum and shift the political weather by following this cycle:

Escalation

Escalation is what happens when people take disruptive action together. A period of movement organizing when organizers take action in a way that uses disruptiveness and sacrifice to attract attention and stake moral claims. Examples of escalated tactics include sit-ins, hunger strikes, marches, and so on. Escalation is always seen in relation to what kinds of actions the movement or group has already gone through – i.e., actions can be planned to escalate over time as demands are not met.

Absorption

Absorption is what happens during and immediately following any escalation. This is the systematic process of bringing newly activated people into the movement so that the movement grows in capacity and can escalate with greater impact over time. Absorption can mean new people signing an online petition, joining a mass call, or attending an orientation training. Good absorption doesn’t just move people onto a ladder of engagement -- it puts them on an elevator of engagement so that the most enthusiastic new leaders can step into high levels of responsibility quickly.

Active Popular Support

Active supporters of a movement agree with a movement’s values and goals, and are participating in sustained action (repeatedly, over time) to advance the movement.

A type of engagement, or consent to the movements/ organization's values, goals by the public that is strong enough to compel them to act through voting, persuading people, protesting, or non cooperating in support of the movement. Often through their engagement with the pillars of support which can include their occupations they work at, the schools they participate with, the government they are citizens of, and the coming. Can be measured through public opinion polling, and collecting data around mass participation in movement.

Passive Support

Passive support for a movement refers to how many people agree with a movement’s values and goals - but aren’t taking sustained action to help push the movement forward. For example, this can be measured as how many people respond to polling in favor of a movement or issues brought up by a movement. A type of support from the public which means they in their personal opinion support the cause of a movement, but does not influence their behavior in any significant way. This type of support can be measured by public opinion polling and often is represented in how someone will anonymously vote on a proposition if they are already planning to vote and the position represents accurately their opinion on the issue for them.

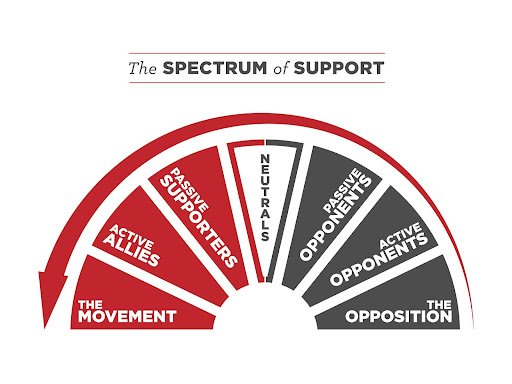

Spectrum of Support

If we know that people have the power, and that we need as many as possible to join the movement and withdraw their consent from the institutions upholding the status quo, we need to be able to assess where the public stands on a given issue.

The spectrum of support is an excellent tool to breakdown the public's position on an issue or movement.

Trigger Events

“A highly publicized, shocking incident that dramatically reveals a critical social problem to the public in a visid way.” - Bill Moyer. Trigger events are the opportune moments of escalation for the movement. They can be completely outside the control or influence of the movement (as with the police murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson) or they can be completely created by the movement (Occupy Wall Street’s Days of Action, Gandhi’s Salt March, etc.). A trigger event is an opportunity to amplify the demands of the movement through escalation. It is important to understand that strategic preparation for trigger events outside of the movement’s influence and strategic coordination of trigger events entirely within the control of the movement are both essential to building enough momentum to win.

Moment of the Whirlwind

A moment of the whirlwind is a period of time in which multiple trigger events are occurring in a short period of time, building off of each other to further shift the political landscape and open pathways for transformation. Typically, it is a moment in which normal approaches or rules of organizing do not apply, and the possibility to quickly shift the public on a critical social issue opens wider than usual. In a moment of the whirlwind, many people who were previously unengaged may be asking "What can I do??"

Mass Training

Mass training asks: what do people need to know in order to join the movement and act in step with its goals and values?

The goals of mass training can be broken down into 3 priorities:

To build the capacity of the movement by absorbing new members and giving them roles

To disseminate the culture and strategy of the movement (its DNA)

To protect the DNA

A good mass training program will have an initiation training that gives new members the basic information (the movement’s basic story, strategy, and structure) and skills (recruitment, action design, etc.) they need to act on behalf of the movement with both autonomy and unity. In addition, a mass training program will have advanced trainings where people can learn to take meet the movement’s needs in greater depth (learning to become trainers, to plan and support large trigger events, to support online infrastructure, etc.)

Movement "DNA"

Leadership in popular movements means creating opportunities and systems for mass participation. In order to do this, leaders must design the “DNA” of a movement cycle so that they can give away the strategy, story, structure, and culture of a movement to hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom will be taking action for the first time. To weather threats and opportunities over the course of several years, strong movement DNA must answer the following questions:

Story: How can we create a public-facing identity and narrative that will inspire people to join our movement and advance a new common sense around our issues?

Strategy: How can we build a multi-phase strategy that withdraws consent from and cooperation with the status quo to effect change in both public opinion and policy?

Structure: How do we create volunteer structures that can scale by absorbing thousands of new members each year and distributing leadership through clear roles, teams, and lines of support?

Culture: How do we design a system of values, principles, and practices that can be disseminated throughout a movement to embody the kind of interdependence and reciprocity we want to see in the world?

Civil Resistance

Civil resistance is a way for ordinary people to fight for their rights, freedom and justice without using violence. People engaged in civil resistance use diverse nonviolent tactics—such as strikes, boycotts, mass demonstrations and other actions—to create social, political and economic change.

Civil resistance movements are powerful because they shift people’s loyalties and behavior patterns. When people in a society choose to withdraw their consent from, and reduce their obedience and cooperation with, an unjust system, that system becomes more costly to operate. When enough people choose to no longer consent and obey, the system can become unsustainable, and it then must change, transform, or collapse. Even when the opponents of civil resistance movements have been well-armed and well-funded, they have often not been able to withstand the sustained mass disobedience and civic disruption caused by strategic, widespread acts of nonviolent defiance. - Hardy Merriman

“Civil Resistance” is much more than protests, marches and civil disobedience. Those tactics are among hundreds that can form the repertoire of independent political strategies for the people of any nation to plan, so that together they can act to win their rights, obtain justice, stop corruption and other abuses of power, and establish or reform democracy.

Many of these movements and campaigns share common dynamic features as a form of political struggle:

They summon and mobilize the participation of ordinary people by expressing their yearning for profound change, and they weld that popular resilience to specific strategies of action.

They create new kinds of political space in societies, by organizing resistance in the arts, education, business and even sports.

They challenge the legitimacy of governments, power-holders or institutions which pretend to hold sway for good purposes but instead betray the public’s trust.

They disrupt the operations of rulers and institutions that refuse to listen and respond to their views and that try to intimidate or hold them down.

They raise the cost of autocracy, corruption and incompetence by distributing resistance throughout a society, overstretching and dividing the loyalty of security and military forces, and by organizing boycotts and other sanctions that target abusive power-holders and institutions.

- Jack DuVall

Researchers used to say that no government could survive if five percent of its population mobilized against it. But our data reveal that the threshold is probably lower. In fact, no campaigns failed once they’d achieved the active and sustained participation of just 3.5% of the population—and lots of them succeeded with far less than that [5]. Now, 3.5% is nothing to sneeze at. In the U.S. today, this means almost 11 million people.

But get this: Every single campaign that did surpass that 3.5% threshold was a nonviolent one. In fact, campaigns that relied solely on nonviolent methods were on average four times larger than the average violent campaign. And they were often much more representative in terms of gender, age, race, political party, class, and urban-rural distinctions.

Civil resistance allows people of all different levels of physical ability to participate—including the elderly, people with disabilities, women, children, and virtually anyone else who wants to. If you think about it, everyone is born with an equal physical ability to resist nonviolently. Anyone who has kids knows how hard it is to pick up a child who simply doesn’t want to move, or to feed a child who simply doesn’t want to eat.

The point here is that nonviolent campaigns can solicit more diverse and active participation from ambivalent people. And once those people get involved, it’s almost guaranteed that the movement will then have some links to security forces, the state media, business or educational elites, religious authorities, and civilian bureaucrats who start to question their allegiances. - Erica Chenoweth

Nonviolent Action

Nonviolent action (also sometimes referred to as people power, political defiance, and nonviolent struggle) is a technique of action for applying power in a conflict by using symbolic protests, noncooperation, and defiance, but not physical violence.

Nonviolent action works by getting a population to withdraw its support and obedience from the opponents. By getting key groups to withdraw their consent, nonviolent action is able to remove the sources of power for a regime or opponent group. - Albert Einstein Institute/Gene Sharpe

Strategic Nonviolent Conflict

“Adherents of principled nonviolence believe that practicing nonviolence is a form of moral commitment; the idea is close to that of pacifism.

Yet, as This Is An Uprising describes, “many great innovators have arrived at the same conclusion: nonviolence must be wedded to strategic mass action if it is to have true force in the world.” That combination is called strategic nonviolence – in essence, nonviolent tactics purposefully used in a campaign against repressive forces.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a man named Gene Sharp was studying Gandhi’s work in India and found evidence that most participants were using strategic rather than principled nonviolence - they did it because it worked, not out of a deep ethical commitment.

Sharp was troubled by his discovery, but realized it presented a great opportunity – “it meant that large numbers of people who would never believe in ethical or religious nonviolence could use nonviolent struggle for pragmatic reasons.” – Ayni, Movement Metrics Research